Rob's Story

“We need to be open about PTSD - other veterans shouldn’t be afraid to ask for help.”

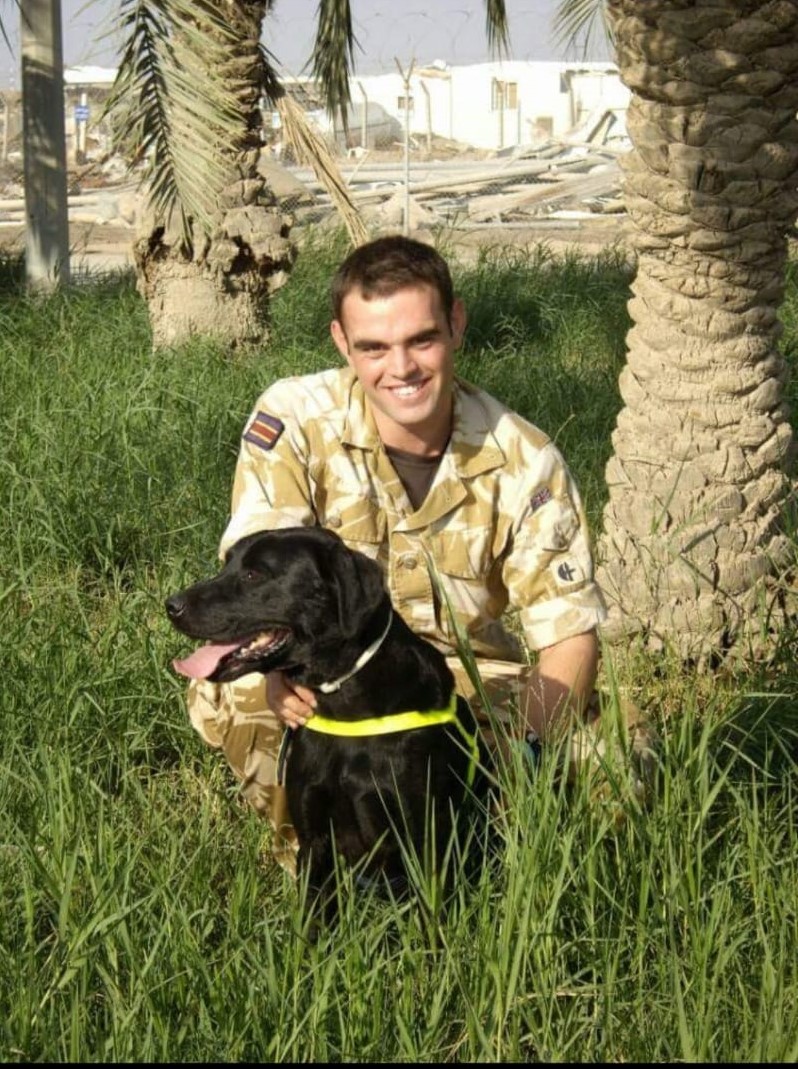

A tour of Afghanistan and a gruelling tour of Iraq left Army dog handler Rob experiencing serious mental health issues and homelessness. Years later, he’s now back working with dogs thanks to Combat Stress’ specialist mental health treatment.

Rob joined the Royal Army Vetinary Corps in 2006 as he wanted to learn a trade. "It was suggested if you want to be the best then join the best, so I joined the Army," he says.

Rob joined as a dog handler, fuelled by a life-long love of dogs. “Working on training dogs was the best bit of my time in the Army,” he says. “When I was seven, I’d pay kids my lunch money to call my name out during the school register so I could go off and play with dogs in the street. So playing with dogs became my job, and my job was my hobby.”

In 2009 Rob and his dog Ted were deployed to Iraq for an arms explosive search role; undertaking patrols, going on operations, making sure vehicles were safe and keeping locals back if they seemed threatening. Rob’s dog was responsible for sniffing out IEDs and keeping his fellow soldiers safe.

“It’s strange how you’re on a lower pay band than the infantry and yet you’re in front of them all, responsible for the 30 lives behind you and you’re trusting a dog,” he says. “It’s hair raising there. When you watch the films and TV you get it in your head it’s dangerous out there, but when you step off the plane it doesn’t seem real.”

Rob says a number of incidents during his four years in the Army had a lasting impact on him. “One of the worst was sleeping and relying on people in your camp to keep the enemy back, then the mortar alarm goes off and your safe place is no longer safe,” he says. “You don’t know where it’s going to land or whether it’s safe when you step outside your tent.”

He shares another incident that stays in his mind – the time someone else took his role on a tour. “Because of the way the dates worked it wasn’t my tour anymore, and so I signed off and the other person went to do my role,” he says. “They went and they didn’t come back. Then you are left with combat guilt.”

Rob was left with thoughts of what could have happened, which were hard to process. “You have these thoughts – the not knowing, the knowing, the should I? What would have? What could have? - in your head from the day you step off the sand back into soil,” he says.

Rob noticed he was experiencing mental health issues when he was still in the Army but didn’t feel he could seek help due to stigma. “I noticed when my dog died because I didn’t have a focal point, or comrade anymore,” he says. “A lot of stuff unravelled. I thought back to when I was on leave and went to a bonfire night display. A rocket had gone off and I was quivering behind a car.

“I put on a stiff upper lip and said I was fine, and my family thought I was mucking about being a soldier saying ‘look how quickly he took cover’ – but I wasn’t playing. Suddenly things fell into place, and I started realising I had a problem.”

When Rob left the Army in 2010 life was hard. “Alarms were triggers for me because they reminded me of mortar alarms in Iraq so I’d try to avoid them.” he says. “I’d try to sleep to escape it, but the old reality is in your dreams and it’s hard when you’re asleep or awake because you can’t escape yourself. The simplest things like going to concerts, things I used to enjoy before joining up became impossible.

“You’re forever living the role whether you like it or not, because it’s instinct. Even when going for a relaxing walk through the woods with your dog, you’re listening for noises, for trip wires, so even the simplest of pleasures can be triggering.”

Upon leaving the Army Rob tried a number of different jobs, including nightclub security in central London but found himself faced with knives and guns again. He also enrolled in a performing arts course because “pretending to be someone else was better than the life I was living” but the kind of roles he was given, such as bouncers and soldiers, were triggering as they reminded him of his time in the Army.

Eventually, with a business partner, Rob set up a successful dog training business but unfortunately this came to an abrupt end during the Covid-19 lockdowns. “It was hard to keep the business together,” he says. “You can’t train dogs if you’re only allowed outside your house for an hour a day. Everything fell apart and my relationship broke down. I moved out of the house and went to volunteer at a vegan sanctuary in Wales, looking after the animals to give me a reason to get out of bed.

“I ended up living in my van and visiting foodbanks to eat. I didn’t feel justified taking food from foodbanks though, I put myself on the lowest rung on the ladder to make sure everyone else was ok. My mindset at that point was to protect those around me over everything else, including myself.”

Rob decided he needed help and having no money on his mobile phone, called Combat Stress’ free Helpline. “From that moment on Combat Stress walked beside me,”

Rob had treatment over the phone for the next two and a half years, including Occupational Therapy and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy appointments. He moved into a new home and found old friends re-entering his life.

Rob’s fiancée Anna took part in our Together Programme, a dedicated programme for the partners of veterans which provides educational information about trauma-related mental health problems, as well as skills and strategies to help them support their loved one, take care of themselves and their family. “It was great as it really helped her to understand how to better support me, rather than guess,” Rob says.

“Combat Stress has got me back to doing the things I enjoy,” he says. “I go for walks, I enjoy fitness. I’m now dog training again and I also teach kids kickboxing to improve their confidence.

“I want to help people understand that there’s light at the end of the tunnel, it isn’t all tunnel like I originally thought. We need to be open about PTSD and other veterans shouldn’t be afraid to ask for help. The armour that you carry and can’t put down doesn’t need to always be with you – Combat Stress can help you to store it.

“I want to say a massive thank you to Combat Stress.”

February 2024